Book Review - The Breaks of the Game

October 26 2014I’ve been meaning to read David Halberstam’s The Breaks of the Game for several years. It’s universally recognized as a milestone in NBA writing. Bill Simmons wrote glowingly about it and frequently references the book in his articles. After finally reading it, I’m happy to say that it’s not just a truly wonderful and descriptive book about life in the NBA, but also in general an amazing piece of writing.

Halberstam spent the entire 1979-80 season with the Portland Trail Blazers. It really shows how much direct access he had with the team and others in the NBA. The entire book is a series of stories and anecdotes from the people he spent time with. Halberstam really digs deep and finds the essence and personality of every player on the team. His writing is very long-winded, but it’s a pleasant contrast from the modern writing that emphasizes conciseness to cater to the short-attention span generation.

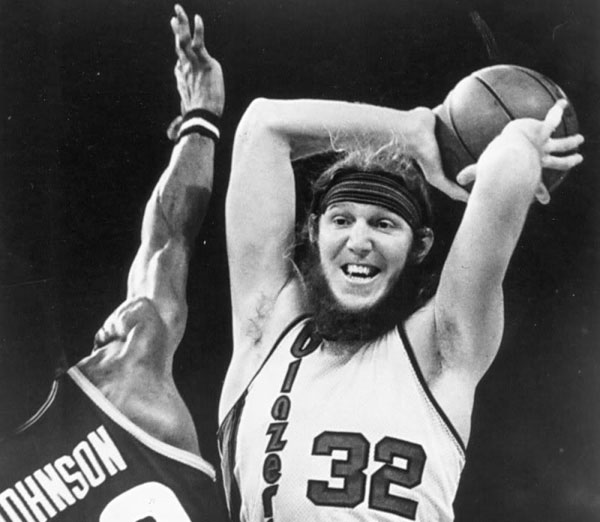

The 1979-80 Trail Blazers are an interesting team to feature. They won the NBA title in 1977 and started the following season 50-10 before Bill Walton suffered a series of foot injuries that eventually derailed his career. For this season, Bill Walton had been traded to the San Diego Clippers and the Blazers were starting an uncertain rebuild. The two main characters of this book are Bill Walton and Dr. Jack Ramsay, the Blazers coach.

Bill Walton is both one of the greatest centers in NBA history AND one of its greatest “what-ifs?”. He was a seven footer that had all the requisite low-post offensive skills and defensive skills to anchor a team’s defense. What separated him was his passing and court vision. The picture below is how I always envision Walton: hands held up high, ready to make the pass. Walton was the perfect high-post center, the player tall enough and smart enough to quarterback an offense. Recently, players like Joakim Noah and Chris Webber have also played this style, but Bill Walton was the original. In this book, we learn more about Walton’s injuries and especially his state of mind in dealing with those injuries. Like Yao Ming, Walton’s body was simply too large for his feet to support him properly. Walton only had a few years of high-level play (at UCLA, the one NBA championship season), but his play was so pleasing and dominant that it left people wanting more. One of the biggest compliments Halberstam pays to Walton is to describe him as a “Basketball Jones”: He was, in the black vernacular, a genuine Basketball Jones, a player who cannot let go, who even after 100 games has to play more, who, even in the off-season, seems to graviate towards a playground.

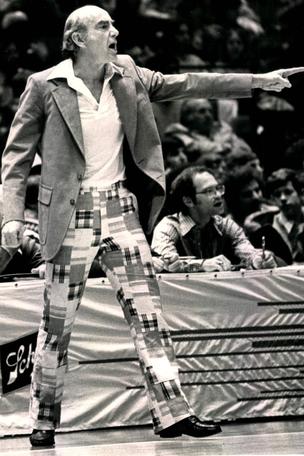

Dr. Jack Ramsay was one of the iconic coaches of the early NBA. He always had the 70’s, ABA “look” with loud suits and pants (Terry Stotts, the current Trail Blazers coach, recently honored Dr. Jack by wearing a 70’s era suit jacket). He was one of the first coaches with a rigid “system”, one based on movement and passing. The 1977 championship battle between the Trail Blazers and the 76ers was billed as the battle between an offensive system versus players that excelled in one-on-one play (that 76ers team had Dr. J, Doug Collins, World B. Free, and Joe “Jellybean” Bryant, aka Kobe’s father). The book does a great job of describing the personal relationship that Dr. Jack had with his players while juxtaposing with his duty to build the right team with the right players, including trading away Maurice Lucas and Lionel Hollins, who were disgruntled by their salaries.

The one other player I found really fascinating is Kermit Washington. I never knew much about Washington as a player or as a person. Like many NBA fans, I knew Kermit as the guy that nearly killed Rudy Tomjanovich in an on-court fight. Washington has the most interesting story of anyone on the team. He came from pure poverty and had no confidence as a kid. When one of his teachers complimented his work in class, all the other children in class laughed because they assumed the teacher was being sarcastic. It’s amazing how far a little self-confidence goes. Washington amazingly didn’t even concentrate on basketball until he was threatened with the prospect of having to move out of his home once high school ended. He crashed an all-star game (literally, he wasn’t on the invite list but talked himself in) and was recruited by a school with barely a basketball program (American). Still, my favorite story about him is how he acted during a long losing streak: during the losing streak he had gone to the library and taken out a biography of Gandhi, hoping to find solace and comfort from the great man’s life.

There are a few broad themes that I found interesting. The first is racism. Basketball, and the NBA, has always struggled with the marketing of primarily black athletes to the widest possible audience. The book is very frank about how black players feel, particularly with regards to competing for roster spots against white players. It was common practice back in those days (and arguably persists today) to keep white players on the team, even for end-of-the-bench roles, to keep season ticket holders happy. The following quote describes the New Orleans Jazz’s pursuit of Pete Maravich.

Because Maravich was white, a local hero, and so flashy a player, the ownership had traded away the future of the franchise - two first-round draft choices, two seconds, and two roster players - to pry Maravich away from Atlanta, where he had already worn out his welcome, and where a comparable management, anxious not to offend its white fans (or, more accurately, hoping to locate them), had broken up a very successful, virtually all-black team, and drafted Maravich out of college.

The second major theme is just how unhappy everyone was with their salaries. At this time, the NBA was just beginning to grow up, with the TV contract constantly being renegotiated, and player salaries were volatile. In a matter of just a few years, the maximum salary for players went from the low hundreds of thousands of dollars per year up to a million. The result is that nearly everyone was unhappy. As soon as a player signed for big money, all of his teammates became envious and started feeling that their contracts were no longer good enough. One of the big subplots of the season for the Blazers was the unhappiness of Maurice Lucas, their best player. They sent Lucas home when the trade rumors became really prevalent, and he was eventually traded to the Nets.

The final theme is just how much of what was happening in the 70’s is still relevant to the NBA today. Some things never go away. It will always be harder to win the second championship than the first championship because players become complacent: The moment a team reached the top, the very mechanism that had worked to pull the players together began to work to pull them apart. Watch out, Red Auerbach of the Celtics had warned Harry Glickman, The Trail Blazers’ general manager, after the Blazers won the 1977 championship, now your troubles begin - they’ll think they’re All-Stars now. It’s also interesting how even in the 70’s the Knicks were known as the team that bought superstars at the expense of team building: The Knicks were shying off Lucas anyway. The idea of paying big money to Portland made them nervous, for they had just gone that route, attempting to purchase a championshipo by going after highly paid superstars. A team once lovely to watch had become a vague assortment of overpaid egotists. The contrast to its predecessor was unusually painful for basketball fans.

Finally, there are a few amazing anecdotes that Halberstam that I had to collect for this post.

On basketball players walking through the airport: “Are you basketball players?” a middle-aged lady had asked Swen Nater as the San Diego Clippers went through an airport and the 6’11” Nater had said as politely as he could, “No, ma’am, we’re not basketball players, we’re gay ice skaters.” At which point Sidney Wicks, standing next to Nater, had pointed to him and added, “And, lady, this big guy really wears me out.” The woman fled.

On Bobby Knight recruiting Isiah Thomas: Then in a dramatic last-minute confrontation, Gregory Thomas, one of Isiah’s older and more volatile brothers, had appeared, and there had been a series of charges and countercharges, threats and counterthreats about Isiah’s future with Bobby Knight. Gregory included Embry and Buckner among the potential exploiters of his brother. Knight, enraged, had finally blown up. “You’re an asshole and you’re a failure, and the worst thing about you is that you want Isiah to fail the way you did.” He turned to Isiah and got up. “If you stay near him you’re going to be ruined. I’m getting out of here. I’m sorry we lost you.” Then he walked out. The next day Isiah Thomas, in tears, had come to see Knight and had pleaded for a chance to go to Indiana. There he had gone and soon he too was fashioning a love-hate relationship with Knight worthy of that between Buckner and Knight.

On Bobby Gross and the essence of passing: On this team he tried to pass and because the others were not passers themselves they were rarely ready to take it. The key to passing was anticipation, two men sensing that the same thing would happen, not that it had happened.

comments powered by Disqus